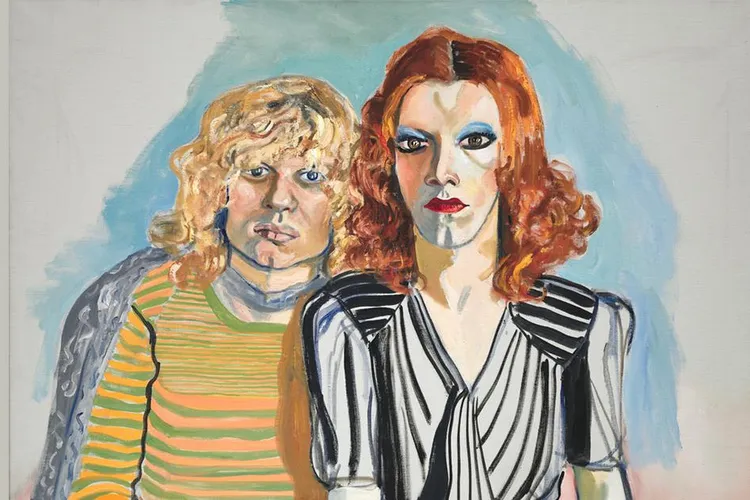

Alice Neel, Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd, 1970

I am trying to really understand friendship (5)

Among friends, there is no planning of friendship. Our best friends were, at a certain moment, strangers. And while most of our encounters either fade quickly or arise from coexistence imposed by needs, circumstances, or interests, friendship germinates and tends to endure; it insists on its quiet presence in the hearts of friends.

Unlike any ideological narrative or description of a utopian future, friendship appeals far more to the present and to memories of the past. In fact, tending to a friendship and preparing it to last into the future is not friendship itself; it does not belong to the nature of friendship, but rather to the fear of losing it. Meanwhile, the memories that constitute the past of a friendship can serve as moments of celebration of that very friendship — an acknowledgment of its continued existence. At other times, when the friendship fades with the passing of time, the only way to revisit it is precisely through the memories shared.

Amid the uncontrollable — the misinterpretation of acts and words despite the best intentions — friendship has a redemptive nature for those fortunate enough to have it present in their lives. Between a friendship and a romantic relationship, even one of love — affirmed, sworn, perhaps even truly felt — the former surpasses the latter in its full acceptance of the other as they are. In this purity of disinterest, friendship shines like a solitary torch in the erratic world and civilization through which we wander. Its value lies not only in the relationship itself, but in the symbolic, collective reach of its disinterested character.

If, as it seems to me, friendship does not occur only among individuals endowed with Aristotelian virtue — that is, it does not require morally virtuous people in order to exist — then its very features, such as wanting the good of the other for the other’s sake, asking nothing in return, and tolerating the absences and silences of our friends (a point to which I hope to return), give friendship a social value: the quality of a community grows in proportion to the number of genuine friendships that flourish within it. Thus, it is not necessarily the case that friendship happens only among good, upright, virtuous people; rather, the community itself becomes more virtuous insofar as authentic and lasting friendships take root within it.

A political community is founded upon an implicit social contract in order to establish social peace and the conditions in which prosperity can grow. If we look at the thinkers who inaugurate modern political philosophy — from Hobbes to Locke and Hume — we learn that law is created to give individuals the conditions to pursue and achieve their own prosperity, on the one hand, and to maintain the stability of society as a whole on the other, so that within it, over time, conditions of peace and progress may be established. In a friendship, the same kind of expectations exist and are lived by each of those involved as implicit and mutually subscribed. However, unlike the structures of political power, friendship requires no imposed hierarchies; it neither requires nor admits any superior or external entity to regulate it, as institutions do with society.

It presents itself as a shared, unplanned experience — a line that runs through our lives, fragile and resilient at the same time. If an imbalance arises, it may break, though not without first reacting with acts of resistance and an instinct for self-preservation, trying to overcome the barrier that threatens to turn it into a memory.

If, though, a friendship is no longer lived but preserved like a fossil of life , this means not that friendship dies, but that it is merely prevented from continuing. Its purity — the purity proper to friendship — remains untouched: friendship does not decay. It endures in its essence, even when it survives only as memory. The purity of friendship, if it is truly friendship, protects its essence, showing it as incorruptible in its substantiality, surviving even its cessation. As with a love story, friendship is worthwhile insofar as it is a shared experience in which two people participate in the essence of life while they still partake in it.

Lived friendship depends on a tacit agreement between friends. It endures as long as its presuppositions are not broken. However, if I speak of the presuppositions of friendship, I imply that friendship exists “in itself,” as a real substance alongside others such as love, courage, beauty, the good — any metaphysical eidos. If friendship can be broken, and if remaining in the relationship implicitly denotes a “contract of expectations,” then we must recognise that friendship is more: it is, substantially, more than its exercise; it is a reality-other in relation to the reality of the relation, within which an essence foreign and eternal is made present.

Friendship is not created by friends, but lived by them — a celebration in which we participate, but to which we may lose access, without the celebration ceasing elsewhere in the heart of the world and in the hearts of other beings bound by that tie.