The beautiful Loeb Classical Library book of the Nicomachean Ethics.

I am trying to really understand friendship (3)

In the past, reflection on friendship has often focused on the proximity of this feeling to the realm of public affairs. This relationship is established by the central idea of some ancient philosophers when it comes to describing friendship between men, and that is virtue. Virtue is the central term of all Aristotelian ethics, and it is easier to understand its axial and instrumental function in this philosopher’s system than to reach a simple definition of its meaning. Since classical virtue, even in Aristotle, is still infused by the adventures and misadventures of mythological tales, there is in it a certain anamnesis of the hero. Ulysses, Hercules, Persephone… remain archetypal figures, not unlike Christ on the cross for a Christian. In these stories there is always a strong element of resistance and sacrifice, aspects that are present, either implicitly or explicitly, in virtue. In this sense, we also discover the links through which political philosophy calls for virtue as a character trait that purges society of evil and bad people, which, as in the epic narratives of the past, ends up including a moral value.

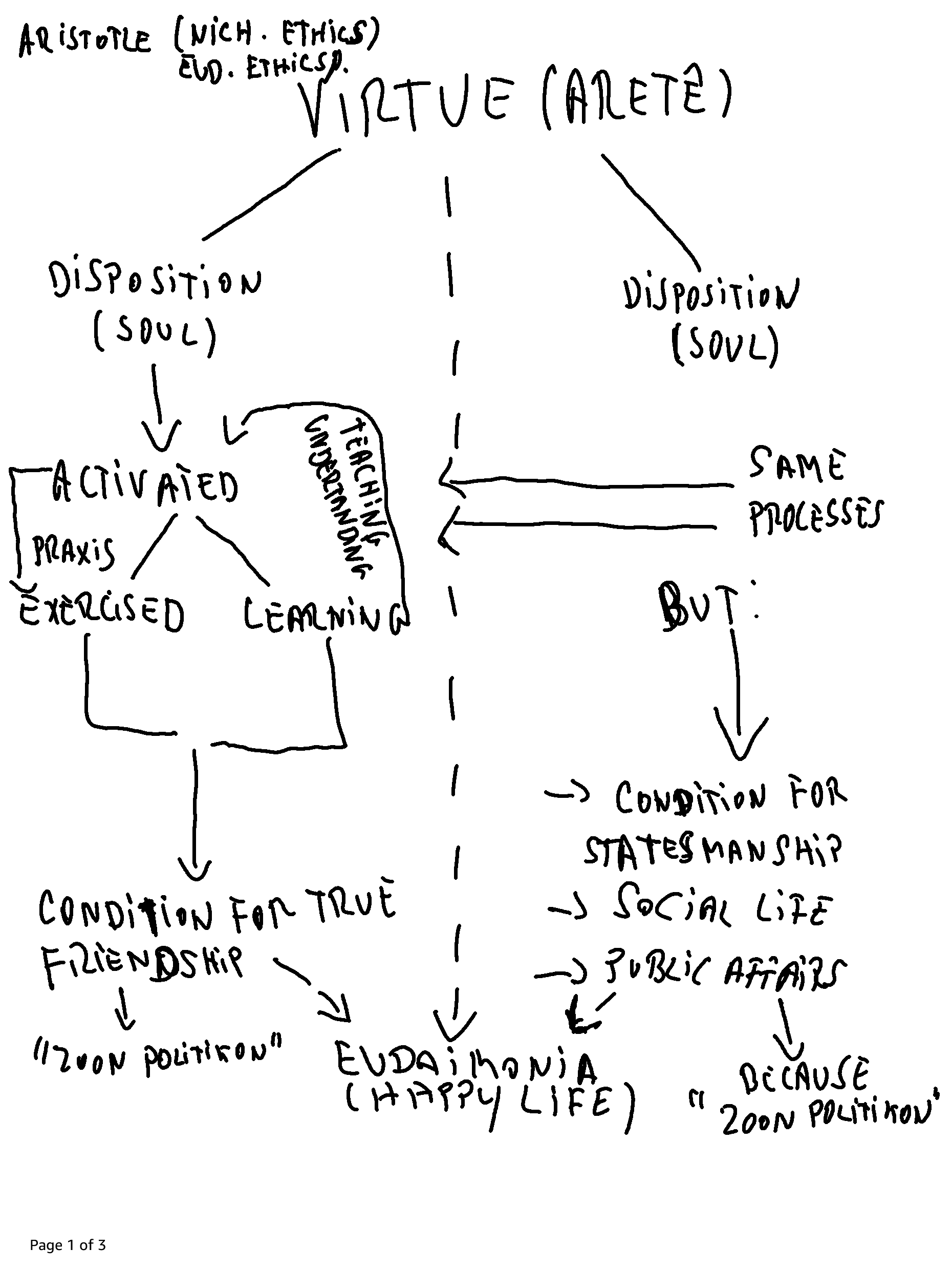

It’s not clear how what Aristotle and others understand by virtue is the fundamental aspect of friendship. Aristotle defines virtue as a „disposition“ of the soul, a potentiality that can be developed or not, although its principle is innate. It is therefore up to each person to become aware of his or her potential and to develop into a virtuous being. Not so much because virtue is an end in itself, but because virtue is essential to the attainment of the greatest good a life can aspire to: happiness.

The characteristics of this “virtue” are temperance, the ability not to be dominated by emotions and not to make decisions based on their immediacy. It’s also about the ability to find “the just mean”, which is one of the most famous Aristotelian maxims.

A very important aspect of the Aristotelian doctrine of virtue is the role of wisdom (phronesis). This is because Aristotle distinguishes between two types of virtues (noetic – which need to be learnt – and dianoetic – which require exercise and the ability to choose well). And it is precisely wisdom that leads to a good choice. It is necessary to learn that each decision varies in its applicability and effectiveness in view of the greater good, happiness. Virtue is the best and most direct path to happiness, to a complete life. And Aristotle sees virtues such as temperance, but also justice or loyalty, as the elements that make up a happy life.

From some of these ideas we can see how what Aristotle calls friendship based on virtue (the only true friendship, as I’ve written here) really depends on the presence of virtue in all the individuals who maintain the bond of friendship. Aristotle implies that friendship flourishes and endures as long as friends base their actions and their relationship on virtue. In this case, the temporal element of friendship alerts us to the fact that it can end and lose its virtuous purity, but also emphasises that friendship (like virtue) depends on choices that may or may not be wise.

If I wrote that ‚it’s not obvious how Aristotle makes virtue the fundamental aspect of friendship‘, it’s because it seems to me that friendship is at least as much about feeling, emotion and intuition as it is about shared values, loyalty in events that require it, or generosity. If this is the case, then friendship crosses the two dimensions of Aristotle’s anthropological vision, in which the human being is distinctly composed of a volitional part, the body, and a rational part. For him, friendship, which is described as genuine if and only if it is based on virtue, results from the rational process of the capacity to be virtuous.

If we reflect on the birth of the feeling of friendship in ourselves, I think it is hard not to find Aristotle’s reflection on friendship somewhat incomplete. The philosopher was definitely more interested in the virtues of virtue itself than in friendship. His ethics is an Ethics of Virtue and has an affinity with Homeric heroism, so it is built on the value of action and not on the comforting confidence of knowing that you have a friend in someone.

If a human being is disposed to virtue, through the natural characteristic of seeking happiness, then friendship is one of the expressions of happiness. Man is zoon politikon, as described by Aristotle, in other words, a social animal. The will to interact and the demand to seek happiness establish the principles by which virtue is the central node of Aristotelian ethics. A characterisation of the nature of friendship from these aspects alone is much more questionable, and leads us to counter-examples and doubts that I will continue to explore.

My biggest objection has to do with this link of necessity between educating the soul to act with virtue (paidéia) and the building of a relationship of friendship with another human being. Aristotle only conceives of virtue as a potency which, when exemplified in deeds, becomes effective in political terms. And amid the formation of a good character and the good government of the city, friendship is shown as the other side of the same coin: ‘[…] it is friendship that holds the city together.’ (Nicomachean Ethics, Book VIII). I’m still trying to understand friendship.