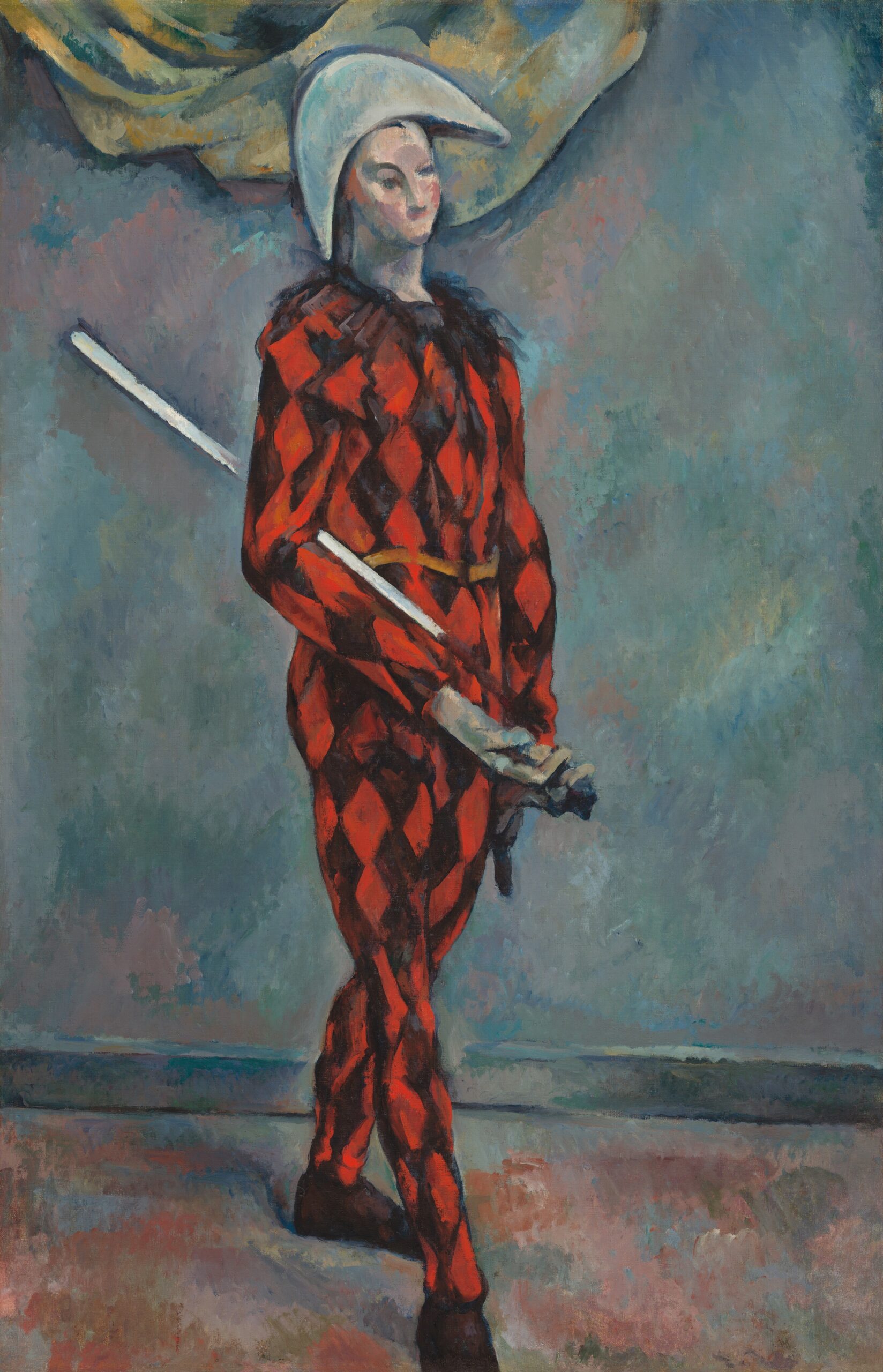

P. Cézanne, Harlequin, 1888-90.

Dare to doubt

“The philosopher is marked by the distinguishing trait that he possesses, inseparably, the taste for evidence and the feeling for ambiguity.”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, In praise of Philosophy.

When I reflect on how the years of study contributed to my life, I always reach the same conclusion:

Learning philosophy is largely about learning how to think and how to pursue clarity in our mind. It does not matter who we are at the starting point, nor what we do, nor what we have dedicated a career to. What is important is the readiness to welcome a study that, through a process involving struggle and even complexity, through reading, questioning and debating, through the acquisition of awareness over prejudices and illusions, confers us the gift of a permanent compromise to knowledge and to the truth.

Philosophy is a power of subjective liberation. And through this liberation, the Self is forced to evaluate upon its own sense of completion, aiding it with guidance towards the path of a meaningful existence – be that as it may –

Be that as it may…as to indicate that being a philosopher does not necessarily turn you into a model of virtue, nor that philosophy provides universal and timeless answers . Acquiring contact with the history of philosophy will rather, in the manner of Socrates, allow you to see why it is an end in itself, how its most originary meaning (a “love for wisdom”: philo-sophia) is already a programmatic awakening. A way of enquiring that, when genuinely delivered, will stimulate your curiosity and act in your mind like the ascension of “Apollo´s carriage”, at dawn, acts in pervading with increasing brightness the early hours of the day.

Out of the many peculiar effects of studying philosophy, one of the most intriguing has to do with the fact that our mind starts to exercise doubt. Not necessarily an intransigent or radical doubt, but a methodic kind of doubt that carries an aim with it. The aim is to self-dissolve into a justified belief about the world, about that very same aspect of the world whereupon doubt was posed. What I want to point out is that, unlike a common conception that sees doubt as a cause of indecisiveness in practical life, or as a sign of a passive character, this philosophical doubt is constructive, because it is the origin of a motion in our mind. A motion that wants to overcome doubt itself and arrive at a strong, perhaps even foundational belief that can reshape, even shift, our understanding of the world.

Therein lies the peculiarity of this essential attitude of a philosophical mind. Doubt is a method for acquiring honest beliefs that shape conceptions of the world, and of ourselves, and our relations. It is a condition for learning, and thus to progress, for there is no possible discovery for a mind who is full of certainties.

The reason I like Merleau-Ponty´s quote at the top of this text is due to its conciseness in regarding the attitude of a philosopher, almost as a description of the exact inner state that accompanies the endeavour into philosophy. Having the sense of ambiguity means no other than becoming aware of deceit, which can be present in many ways: sometimes by the simplest perceptions of our senses, sometimes through misinformation spread on a social network, other times even because something false, wrong or thought-misleading became part of a tradition.

As Merleau-Ponty points out, the sense of ambiguity and the taste for evidence are inseparable and constitute one single event. Lying in the center of this convergence is the active, progressive, philosophical way of doubting. It is scepticism that initiates a keenness, if not a spiritual affinity, towards truth.